Anthony Arratoon Anthony was born in Persia in 1813, the son of Arratoon Anthony and Vartkhatoon. With his family, he moved to India in his early years, where he was to meet and marry the fifteen-year-old Mariamjan Ter Stephens, at the Armenian Church of Nazareth in Calcutta in 1832.1 Shortly after, the whole family moved to Penang (then known as Prince of Wales Island) in The Straits Settlements in northern Malaya. There is evidence to suggest that both he and his parents travelled between Penang and Calcutta on several occasions over the years. Like so many of the Armenian diaspora, though small in number, they made a lasting economic, cultural and religious impact on the community in Penang, which continues to this day. The Armenian immigrants to the Malayan Peninsula were responsible for the setting up of The Straits Times; for the erection and consecration of the Church of St Gregory in Singapore; for the establishment of the Raffles and the Eastern & Oriental hotels and even for the hybridizing of the Vanda “Miss Joachim” orchid, which was to become the national flower of Singapore.2 Anthony Arratoon Anthony was also the founder of the stockbroking firm A. A. Anthony in Penang in 1840. Subsequently, A. A. Anthony was to become A. A. Anthony Securities Sdn Bhd in 2002 and, in 2012, was amalgamated into the firm of UOB-Kay Hian Holdings Ltd in Singapore.3

Joseph Manook Anthony was the seventh of thirteen children that Anthony Arratoon and Mariamjan were to conceive and he was born in Penang in June 1847. By this time, A. A. Anthony had become a leading financial establishment in Georgetown and its founder a highly respected member of the business community. For many years there was a theory that Armenian Street in Georgetown was named after the many Armenians that had settled there in the early development of the town. However, it later became clear that the name referred to the fact that a specific Armenian had built a home there. More significant is the fact that Clove Hall, which now resplendently exists as a boutique hotel, was built by Anthony Arratoon Anthony and Arratoon Road, just off Burmah Road, was named after him.4

Joseph married Isabel Marion Hogan in 1870 but she was to die only two years later, shortly after giving birth to their third child, Annie Elvira. Of their three children, both Annie and Anthony Stephen died in the 1920s, at 51 and 49 respectively, while their middle child went on to live until 1955, dying at the age of 83. In 1879, Joseph remarried, this time to Regina Gregory, in the same church in Calcutta in which his parents had married 57 years earlier.

Joseph continued to work in his father’s stockbroking firm and to manage the plantations which had been acquired over the years but, in the same year that Joseph’s first wife died, Anthony Arratoon also passed away. Clearly, 1873 was a tragically memorable year. Joseph had already left the Clove Hall family home in 1870 and taken up residence in “Orange Grove” in Northam Road. After the death of his wife and father in 1873, and his remarriage in 1879, he and Regina moved to “Sans Souci”, also in Northam Road, where they were to live for the next 21 years and in which their six children were born.5

Regina was to give birth successively to her children by Joseph at “Sans Souci” almost every year between 1882 and 1891. The first was Elizabeth Catherine (“Katie”), who was to migrate to England and die in 1924 in Chelsea, London. In fact, Katie was a talented writer and wrote the lyrics to at least one of her younger brother Marc’s compositions. In 1883, Margaret Barbara was born and was to die in 1942 in a Japanese internment camp in Sumatra. Alexander Gregory (“Alec”) was born in 1884 and later moved to Singapore, where he died in 1933. In 1886, John Gardener (“Jack”) was born and he also subsequently moved to Singapore and died in 1918. Helen, the fifth child died in 1888, before the age of one. The last of their children, born in 1891, was Robert Marcar (“Bob” or “Marc”) Anthony, who is the subject of this brief biography.6

Sir Frank Swettenham, who had been resident in the Malay Peninsula since 1871, was, subsequently, the Resident-General (1896-1901) and the Governor and Commander-in-Chief (1901-1904) of The Straits Settlements.7 There’s little doubt that the Anthony family, being prominent citizens, would have known Sir Frank at a social and even a personal level. It is highly possible that the Governor, who was a former pupil (FP) of the Dollar Academy (then called the Dollar Institution) in Clackmannanshire, Scotland, recommended the school as a possible destination for the [male] Anthony children.

Be that as it may, Anthony Stephen (born 1871), Alexander Gregory (born 1884), John Gardener (born 1886) and Marc were all sent to Clackmannanshire, where they boarded at Argyll House (run by a Mrs Millen until around 1905 and, subsequently, by a Mrs Gibson) and attended the Dollar Academy. Marc arrived at Dollar in 1899 at the age of 8. His elder brothers had already moved on but John, who was then 12, was still recorded as being at the school, also boarding at Argyll House. John and Marc were also both recorded as pupils at the school in the 1901 Census data for Scotland.8

It was quite apparent, even at school, that Marc’s interests lay in the musical and theatrical world. Evidence of this can be seen from his early-acquired hobby of collecting photos and photo postcards of prominent actors and actresses. Indeed, many of his family and friends assisted him in building his collection by sending picture postcards to him at Dollar. Two of his most prolific correspondents were a “Daisy R.” and an “Alice”. Since the early ones are addressed to him at Argyll House in 1904, it would appear that this interest in collecting such memorabilia began when he was around thirteen years old.

Much as Marc enjoyed his time at Dollar, he was only an average student academically and, apart from a little golf (which he tried his hand at in 1907 and 1908), he was not at all sporty, unlike his brothers. For example, John was the captain of the Cricket 1st XI and the Rugby 1st XV in 1904. Nevertheless, Marc would sometimes go to Edinburgh or Glasgow with the sports teams, attend a matinée of a musical comedy while they battled and, when they returned to school, would sit down at the piano and play the tunes he had heard by ear.9

Though Marc occasionally returned to Penang during the long school vacations, most of the time he would either remain at Dollar during the holidays or take up residence at the Davies Hotel in Brompton Square in London. Being in the heart of the cultural capital of the country at this stage of his life provided Marc with all that he could have wished for and he frequented the theatres and music halls at every opportunity.

In June 1907, Marc attended the opening night of the London production of The Merry Widow by Franz Lehár. Not only did he fall for the music and thereby become a lifelong fan of the operetta, but he also enjoyed the magical performance of the beautiful star of the show, Lily Elsie. Marc attended 66 performances of the show during his 1909 school holidays. As Marc recalled, the final night of the long run of this show was so great that people paid £50 for a stall seat and the boxes were going for £100.10 It was perhaps a portent of things to come as he was to work with Lily in future years and they were to become close friends. It was enough for Marc at that time to realize that this was the style of music that he most warmed to and was to give inspiration to many of his later compositions.

Ironically, even after graduating, he continued to live for much of the time in Dollar, where he became very active in the musical activities of the school. For example, on May 18, 1911, Marc sent a postcard to his mother11 at “Chatsworth” in Penang that he had

been busy at Bank with inspector. Will write next week & tell you all about the Cadet, Dance, Sports and Tennis Concert, in which I am taking part, all these things taking place this week.

The last extant postcard that Marc received at Argyll House was dated February 17, 1912, and was a card to wish him many happy returns for his birthday. It was in this year, when he was 21, that he eventually left Scotland and returned to Penang.

Marc’s musical talent was extremely unusual, as was foreshadowed while still at school. He had no formal musical training and, in fact, was unable to read or write music. However, he had perfect pitch, an extraordinary memory for a melody and the uncanny ability to play it on the piano once he had it in his head. Back with his family, and living at “Chatsworth” in Northam Road in Georgetown, Marc began to establish himself in the social and musical scene in his home town.

He played piano professionally and set up his own small group of musicians, which became popular around town for special occasions. Although his father had hoped, as would most parents, that he would have returned to take up a position in the business, Marc was determined that this was not for him as he felt he had neither commercial aptitude nor inclination. As he was to recount many years later, he was made to try his hand at banking and accounting, but clearly had an aversion to both. Through the good offices of fellow Armenians, the Sarkies brothers, who had set up the famous Eastern & Oriental Hotel in Penang, his father was able to help Marc find the opportunity to lead the band there and he became the conductor of the E & O Orchestra, which performed in the Palm Court of the hotel. This group was eventually to become the Penang Philharmonic Orchestra.

Marc had clearly by this time started to write music seriously, as his correspondent Daisy wrote to him in 1914 from Scotland12 stating she

will look forward to getting the music and will take great care of it and will be sure to give you my candid opinion!!

An interesting insight into the family dynamics can be interpreted in a postcard that Marc wrote to his mother, who was on a trip to Davos in Switzerland in 1915. Marc wrote:13

I have just got The Dancing Masters waltz and vocal score. The waltz I think heavenly. It only came yesterday. Been having a heavenly time of it lately. Dot and Emmie lunched with us today; between the courses I played and they danced. Ripping fun. Dot loves this place. I played for The Importance of Being Earnest done by some amateurs for two nights. I played between the acts. Was at supper party at Newberries after play last night. Got home 2.30. Manook mad. Love RMA.

There was an amateur performance of Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest on December 9 and 11 that year, put on by a group of Kuala Lumpur amateurs. It was the first three-act comedy performed in the city and was in aid of the War Relief Fund.14

The fact that Marc, now 24, referred to his father as “Manook” and that his father should have been mad at him for arriving home late, suggests a fairly strict and formal household, even for the Edwardian period.

In 1919 [after the death of his father in 1917], convinced that there was no future for a budding musician in the Far East, and wanting desperately to focus on composing his own music, Marc set off back to England by ship, with a few hundred pounds in his pocket and his talent — the former coming from a generous legacy and, fortunately for him, having been born with the latter. His original intention was to take up the formal study of music once he arrived in London but, as we shall see, this never materialized.

England in the early 1920s was still coming to terms with the end of the war. Those young men, and women, who were fortunate to have survived the horrors of the fighting and those others who had either lost their loved ones or seen at first hand the horrific injuries of the returning wounded, were looking at the world through the prism of their own mortality. Life was short and was now for living and they wanted to make the most of it.

When Marc arrived in London, the boom in drinking clubs, coinciding with the inventive creation of a mixture, referred to as a “cocktail”, was changing the night scene in the major cities. The young affluent looked to these as an escape from reality and jazz clubs, speakeasies and many less salubrious venues were opening up in quick succession.

But it was also a time of high unemployment and, for the next decade, things were only going to worsen as the industrial powers, which were facing outmoded and loss-making technologies, headed towards the Great Depression. As Marc returned to what he considered to be his real home, there was an extended period of strikes, a jobless rate that reached 2 million in England alone and a divided community that was split between those who had money to spare and those who couldn’t make ends meet.

Not that all was doom and gloom. Society was moving from a predominantly low end manufacturing base to one that was benefiting from the growth of new scientific developments, audio-visual technologies and a wider access to all forms of entertainment, all of which were enjoying remarkable rebirth after the war years.

Of particular benefit to a young musician arriving in London at this time was the fact that young people, enjoying a Bohemian approach to life and an attitude of “anything goes”, were flocking to dance halls and listening to dance music on the radio and the gramophone. Light music, just the kind that Marc was appreciating and writing, was the rage and he was able to fit right into the swinging London social scene.

When Marc arrived, he stayed briefly with his sister Katie (who had already moved to London and lived at that time in Chelsea), while he searched for his own accommodation. When staying in Brompton Square during the Dollar holidays, he had spent a lot of time walking around the King’s Road area and had determined even then that, were he to return to London, this was the place in which he would live. In 1920 he took up residence in a flat at number 10 Glebe Place, just off the King’s Road in Chelsea. He was to remain in this house, the architecture of which he said he fell in love, for the remainder of his life. Although his accommodation was on an upper level of the building, he did for a time live in the basement flat. However, that did not suit him as he found it “rather dark and dismal” and so, when the second floor apartment became available, he took on the initial lease for 12s 6d per week.15

Glebe Place in the 1880s was internationally famous as the arts centre of London. In Glebe Place Studios, half way down the street, artists such as Walter Sickert and William Rothenstein and the book illustrator Ernest Shepard took up residence and Francis Bacon lived at 1 Glebe Place in the 1930s.16 It is unsurprising that Marc felt very much at home in this part of Chelsea.

Marc’s first break in London came in February 1920. Sir Oswald Stoll, the impresario and theatre manager, hired him to produce a piece of music for his “Young Composers” series at the London Coliseum. The programme notes for the performances on February 9 and 16, 1920, show that Marc had entered two pieces: an Hawaiian Melody named “Wai-ki-ki” and the song-ballad “If You Could Come to Me” (with lyrics by his sister Katie Anthony). Ethel Peake, who had popularly sung lieder by Brahms, Strauss, Schubert and others at the 1912 Promenade Concerts and, in 1919, had appeared again at the Proms singing from Strauss’s “Samson and Delilah”, performed the songs.17 The programme notes18 went on to say that

Mr Anthony works by ear alone and it is notable that he rarely loses a melody after it has occurred to him. He uses a musical shorthand of his own invention.

In a later performance on March 8, 1920, he presented a new composition called “Humpski Jazz”, though now he was clearly no longer a new discovery. He now had his own separate billing and there was another “Young Composer” by the name of James Lyon, who was to go on to write four operas and a good deal of chamber and orchestral music.19

“If You Could Come to Me” (see Appendix for sheet music) became a sensational hit and was frequently played throughout the country, largely through the auspices of the Moss Empires, which, in 1899, had joined forces with Stoll’s theatres to produce the largest chain of theatres and music halls in the world. During November and December, from the Nottingham Empire in the north to the New Cross Empire in London, May Robertson sang the song, always accompanied by the composer. So popular did this first published composition of Marc’s become that, in the space of a few months it had been performed by Daisy Leon, the American actress who had just joined the cast of “Whirligig” at the Palace Theatre,20 Eleanor Paget, the opera singer Gertrude Kaye and Ethel Royston.21

On New Year’s Eve of 1920, the song appeared with great success on the bill of the Elysée Restaurant, sung by Mary Pitcairn, and The Concert World argued that this “new composer is likely to make himself well known to concert artistes”.22

It was in 1921 that Marc decided it was time for him to have someone not only to negotiate his terms (which he knew he was incapable of doing effectively) but also to find him work. He approached Leslie Cardew of 23 Gerrard Street, who took on the role of his business manager.

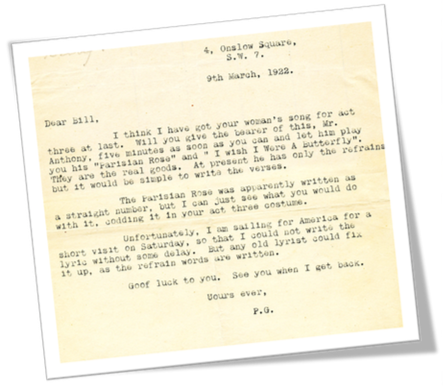

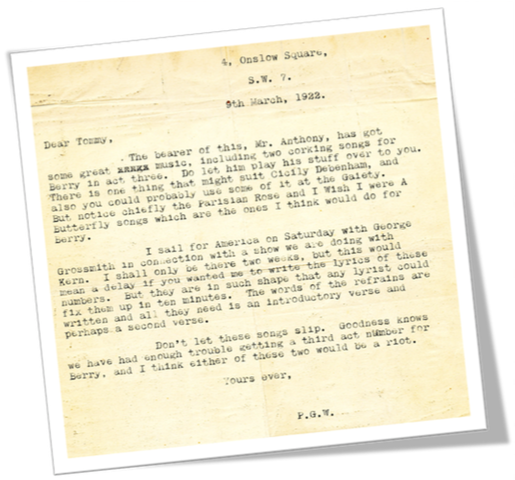

During this year, he composed two numbers, which caught the eye of several people, including the novelist and comic writer P. G. Wodehouse. One of Marc’s challenges throughout his life was to find lyricists who were able to do justice to his melodies and, on this occasion, March 9, 1920, Wodehouse wrote to the comic actor W. H. (William Henry) Berry, who had worked with George Grossmith, the actor-manager, and who was looking for a song for the final act of a new production. Wodehouse believed that he had found the right material in Marc’s “The Parisian Rose”. He also referred to another song, “I Wish I Were a Butterfly”, and said that both were “the real goods”.23

During this year, he composed two numbers, which caught the eye of several people, including the novelist and comic writer P. G. Wodehouse. One of Marc’s challenges throughout his life was to find lyricists who were able to do justice to his melodies and, on this occasion, March 9, 1920, Wodehouse wrote to the comic actor W. H. (William Henry) Berry, who had worked with George Grossmith, the actor-manager, and who was looking for a song for the final act of a new production. Wodehouse believed that he had found the right material in Marc’s “The Parisian Rose”. He also referred to another song, “I Wish I Were a Butterfly”, and said that both were “the real goods”.23

On the same day, Wodehouse also wrote to the producer at the Gaiety Theatre referring him to Marc’s “two corking songs” and asking him to let Marc play ‘his stuff over to you … but notice chiefly the “Parisian Rose” and “I Wish I Were a Butterfly”‘. Wodehouse was of the view that one of the songs might suit Cecily Debenham, who had appeared in Albert de Courville’s Box O’ Tricks at the London Hippodrome in 1918.24 Wodehouse went on to say that he was to sail imminently for America with George Grossmith, hence unable to write the lyrics himself, and that they were to meet up with Jerome Kern, presumably to work on their next show, The Cabaret Girl. He ended the letter by saying that “I think either of these two would be a riot”.25

But living in London and waiting for the day of recognition was never going to be easy. Despite his many supporters and the wide recognition of his talent, this was not bringing in the bacon and Marc needed to find regular work that would provide him with both a steady income as well as the flexibility to compose and develop his skills.

Although Ascherberg, Hopwood & Crew Ltd were Marc’s first publishers and brought “If You Could Come to Me” to prominence, Cecil Lennox Ltd issued music by Marc in early 1922, including a very successful number that was to be heard at his first club venue — The Ham Bone Club, which was situated in Ham Yard, the epicenter of the club scene for what were known as the BYP — the Bright Young People. In The Actor magazine, a reviewer expressed his opinion26 of Marc’s potential by writing that

although he has not been here long, he is already establishing himself as one of the creators of light music and those who are judges are realizing that here is a personality of which some notice must be taken.

Discreet but stimulating clubs, often skating close to the edges of the licensing laws, flourished in London after the 1st World War. Over 50 clubs, which were largely patronized by socialites and young people looking for a good time, operated in the city in the early 1920s. Of course, they were also attractive destinations for the performing arts professionals who would find them a fun-filled respite after the evening shows. The Kit Kat Club was perhaps the most famous but, close behind, was the 50/50 Club, which was owned by Ivor Novello. It was rumoured that the name reflected Novello’s ambiguous sexuality. There was also Rector’s on the Tottenham Court Road and the Gargoyle in Meard Street. Amongst this plethora of meeting spots was The Ham Bone Club, at which Marc Anthony became a musical feature during 1922 and 1923.

In 1923, the magazine journalist and author, E. P. Leigh-Bennett, wrote a wonderfully descriptive article about The Ham Bone Club in the Bystander, in which he described the colourful and devil-may-care flavour of the club. It brilliantly conjures up the night life atmosphere of an alternative London in the 1920s.27

There comes a phase in the life of the hardened night-bird when, sated with the pomp and circumstance of dress shirt and decorum, and longing to be entirely natural and to smoke a pipe for a change, he seeks to creep away to the place where all men are equal and at ease. In such a quest, he finds “The Ham Bone”. From the Circus of Signs you dive into the dark waters of Ham Yard, wherein plutocrats park their cars and at the insidious door in the corner you put away childish things of the West End, cease looking darkly through the glass of fashion and see face to smiling face — with all your sisters! Be under no illusion that, because you may live in Park Street, and drive to Goodwood in a nickel-plated Rolls, that you can stroll placidly into The Ham Bone Club on the strength of your pass-book. There will be nothing doing. The Cerberus halfway up the narrow stone stairs will stare blankly at you. You may, if the gods are kindly disposed, be taken there by a member and then you will see, possibly for the first time (which will do you a power of good) what a leveller of the social status true Bohemia can be. We are no respecter of personages. Our motto is “Live and Let Live” and we enjoy a short life merrily in what was once an old warehouse lying glum behind the glitter of Piccadilly but which, artistically camouflaged, is now our small and intimate dance club.

After describing many of the people whom one might find in the club he concludes with:

But of our charity let us remember that we are at least unique. Some of us may have faces, which repel what we should call threepenny ha’penny journalists. Yet we have a high camaraderie and a low subscription. And we are proud of it. Scipios, of the yellow plush and plutocracy, cannot say as much as that. Not even the Emblematic, which typifies to us nothing but Bradburys and boredom. We are above and beyond them all, because we are cheap and exclusive. Whereas they — they are rich and repulsive. Rather a devilled kipper for ninepence and a kiss to follow, for which there is no payment save affinity, than a lobster cardinale and confusion, when the bill is unfolded. And our faces? Well, those who don’t know them, don’t miss them. But those who can’t see them when they want to (which is often) miss them horribly. Ask our friends — and our lovers.

This then was the establishment to which Marc gravitated and of which he was to become a singular personality and where he was to create his own magical corner in which to build a following for his music.

In 1922, Marc composed the music for a song called “Non-Stop Love” (published by Francis, Day & Hunter; see Appendix for sheet music), which was performed in the show Biffy at the Garrick Theatre Club. One critic wrote that “Non-Stop Love” should “have a great vogue, but it was tantalizing to have no more.”28

In 1922, Marc composed the music for a song called “Non-Stop Love” (published by Francis, Day & Hunter; see Appendix for sheet music), which was performed in the show Biffy at the Garrick Theatre Club. One critic wrote that “Non-Stop Love” should “have a great vogue, but it was tantalizing to have no more.”28

The singer was Teddie Gerard, who had, a few months prior to this, been a member of the Ziegfeld Midnight Frolics at the New Amsterdam Theatre in New York. Miss Gerard had left for America believing that she would achieve greater success there but became disillusioned and returned to her home country.29

Robert Hale, who was also in the cast, presented Biffy at the Garrick and it was a very successful though trivial comedy. According to a review in The New York Clipper, the plot dealt with two partner husbands, who, in order to have a good time, invented a business interest in London, with a partner there called Biffington, better known as Biffy. However, the Biffy of their imagination becomes a reality and the real Biffy imposes on the two gentlemen certain obligations that turn to farce. Also in the cast were Stanley Cooke, Charles Piggott, Maude Hope and Dorothy Fane.30 One is tempted to say that the plot is closely reminiscent of Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest!

The success of Biffy and Marc’s particular musical contribution drew the attention of the theatre manager and impresario, Albert de Courville. In early May 1922 they arranged to meet and de Courville not only bought three of Marc’s songs but also gave him the lyrics to a song called “Hustle With Your Bustle” and asked him if he could write the music to it.

Marc immediately sat at the piano and composed the music, which de Courville liked and asked Marc to transcribe. “I can’t”, said Marc, “I don’t know how to write music!”. He grabbed a taxi, rushed to a music publisher and had them write down the melody whilst he played it still fresh in his head. The veracity of this anecdote was confirmed when de Courville himself remembered the episode and wrote about it in his column in The Illustrated Sunday Herald in 1926.31

De Courville wanted Marc to write some music for his new “Rainbow” show at The Empire Theatre. The star was Daphne Pollard, the Australian-born Vaudeville actress, who had already given 648 successful performances in the role of “She of the Tireless Tongue” in de Courville’s lavishly-staged revue Zig-Zag! at the Hippodrome.32 In this show, she was to perform Marc’s “Hustle With Your Bustle”. According to the reviewer in The Standard on May 14, 1922 “Miss Pollard is wholly delightful”, especially in her “Bustle” scene and whatever pleasure one got from the evening was due to her.33

In the same year, André Charlot, the French impresario, who had moved to London and was staging musical revues between the early 1900s and the late 1920s, asked Marc to write some music for a new show he was producing called Yes … !. One of the lyricists for the show was Douglas Furber, who was to go on to write the famous “Lambeth Walk” in 1937. The other was the Australian, Dion Titheradge, whose most famous song was to be “And Mother Came Too”. Yes … ! was performed at the Vaudeville Theatre in September 1923 and followed a less than successful run of Rats in the same venue. Marc’s contribution was a song called “Sympathetic Jane” (see Appendix for sheet music) and was said to have been one of the “most tuneful melodies” in the show.34

In the same year, André Charlot, the French impresario, who had moved to London and was staging musical revues between the early 1900s and the late 1920s, asked Marc to write some music for a new show he was producing called Yes … !. One of the lyricists for the show was Douglas Furber, who was to go on to write the famous “Lambeth Walk” in 1937. The other was the Australian, Dion Titheradge, whose most famous song was to be “And Mother Came Too”. Yes … ! was performed at the Vaudeville Theatre in September 1923 and followed a less than successful run of Rats in the same venue. Marc’s contribution was a song called “Sympathetic Jane” (see Appendix for sheet music) and was said to have been one of the “most tuneful melodies” in the show.34

The following year, Charlot took a group to Broadway for his Revue of 1924, which ran in repertory at the Times Square Theatre and the Selwyn Theatre from January to September of that year. This review had a glorious line-up of talent, with music by, amongst others, Ivor Novello and Noel Coward. Marc’s associates, Dion Titheradge and Douglas Furber, wrote some of the lyrics and the show featured Gertrude Lawrence, Beatrice Lillie, Jessie Matthews and Jack Buchanan. The following year, Charlot brought the show back to London as André Charlot’s Review, 1925.35

Marc’s professional relationship with André Charlot was to be fairly brief, though they remained friends even after the latter left for America. Charlot’s theatrical life was one of huge contrasts. Although he was the man who gave the 16-year-old Beatrice Lillie her first stage role, discovered Jessie Matthews, Gertrude Lawrence and Jack Buchanan amongst others, he became a bankrupt, a bit player in minor American films and his final days were spent at the Motion Picture Country House (which was a kind of charitable home for retired theatrical people) in Los Angeles.36

The Ham Bone Club, which had opened only a few months before Marc became the resident pianist, was originally founded and presided over by the painter Augustus John and, through him, attracted a largely artistic and certainly hedonistic clientele. Radclyffe Hall, the celebrated writer was a frequent visitor, as was Ethel Mannin, the author and travel writer, who was supposed to have enjoyed dancing there and described the place as “chronically Bohemian”.37 Now that the Charleston dance had found its way from America, it became quite clear that the small dance floor of the club was quite inadequate to provide sufficient space for the new craze. So, in July and August 1923, having become a victim of its own success and due to its popularity, it closed for renovations to be opened again on September 1. Many of the Bohemian regulars contributed ideas to the new décor and, in fact, Marc suggested the colour scheme for the new crockery in the restaurant.

While all this was going on, one of Marc’s earlier pieces, “Parisian Rose”, which had been highly recommended by P. G. Wodehouse, was to form part of the “Rector’s One O’clock Revue”. Cabaret had been growing in popularity and the Rector’s Club on Tottenham Court Road was the centre of this popular form of entertainment. Carl Hyson, the Canadian-born husband of actress and singer Dorothy Dickson, was one of its leading producers. Also on the bill at the performances held in the autumn of 1923, was May Vivian, the accomplished dancer, who had recently been appearing in the Cabaret Follies. Shortly after her appearance at Rector’s, she was to be tragically shot dead in the South of France by a jealous suitor during a season in which she was appearing at the Riviera Palace Hotel in Monte Carlo.

Performing Marc’s “Parisian Rose” was Cecile Maule-Cole. She had appeared in the original London production of Cabaret Girl the previous year; was to star in Poppy in London in 1924 and 1925 and go on subsequently to perform in the Ziegfeld production of Noel Coward’s Bitter Sweet on Broadway. The “Rector’s One O’clock Revue” on this occasion finished with a grand finale, in which the whole company performed “Parisian Rose”.

In February, 1924, Marc wrote the music and Eric Fawcett the lyrics for a new cabaret entitled “Dolly’s Revels” at the Piccadilly Hotel. Edward Dolly, the brother of the famous Dolly Sisters, staged the show and it was launched on February 8, 1924. The show included the popular singing duo Norah Blaney and Gwen Farrer. Also appearing were the eight Dolly Girls. Alex Hyde, the jazz bandleader and violinist and Jack Hylton and His Band, provided the music in the Ballroom.38

By early 1924, Marc had moved on from the newly renovated Ham Bone Club, which still drew its fair share of “long haired men and short haired women” as one columnist described it, and was now the resident “Jazz Wizard”39 at the Bullfrogs Club in Soho. Another writer states40 that it is

an amusing place, which you reach down an alleyway and up a twisted iron staircase and, in the corner of the centre room, Marc Anthony, vibrant as a banjo wire, holds his crowd with piano as firmly as Lopez holds his with a full-size jazz band.

Or, as the correspondent for The Argus, who was visiting London from Melbourne, Australia, to review Wagner’s Ring Cycle at Covent Garden, wrote:41

A diner de l’opera is necessarily short, and the chef usually names his dishes after the opera stars or the leading characters. The light dinner in turn necessitates a souper de l’opera after the curtain-fall, possibly in one of the Bohemian restaurants or dancing clubs of Soho, say the Bullfrogs, where the midnight kipper is served, or a comfortable dish of bacon and eggs. Miss Eve Grey, the young Australian beauty, who has just scored a success at Daly’s Theatre by virtue of her fresh charms, is one of the patrons of the Bullfrogs. The club caters for stage and literary or musical folk, who unite an interest in art with happy Bohemianism. A couple of hours song and dance at a little Soho night club is a welcome relief after six hours of the Götterdämmerung.

The Ball Room magazine41 went so far as to describe Marc Anthony as

a luminary of our own small but growing Tin Pan Alley. He has done numbers for Charlot’s new revue. Daphne Pollard is putting over a fox-trot song of his in the very heart of New York’s jazzland, in the Greenwich Village Follies. “Dancing Jim” and “Hustle With Your Bustle” are two more of his winners. One of these days you will probably hear an enormous burst of revelry from the Bullfrog. It will be the Bullfroggers celebrating their pianist’s arrival in the ranks of the jazz kings with a thing as tremendously successful and lucrative as “Tea for Two”.

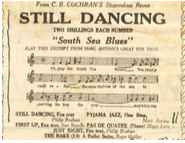

By the end of 1925, there were compositions of Marc’s in shows on both sides of the Atlantic. Charles B. Cochran’s new edition of On With The Dance, which he called Still Dancing, at the London Pavilion featured his “South Sea Blues”43 and his “Pyjama Rag” one-step.

He had also written numbers for a new musical play called Riquette, which was on at the Glasgow King’s Theatre. These were “Picasse” and “When the Telephone Bell Rings”.

Yet another piece, “Teach Me To Dance” (see Appendix for sheet music), was featured in Yvonne, which was written by Percy Greenbank, Jean Gilbert and Vernon Duke. It opened at Daly’s Theatre off Leicester Square in May 1926 and, after its London run, it went on tour throughout the country. In the same period, some of Marc’s music appeared in Suzette, which was playing at the Gaiety Theatre.

One of Marc’s early childhood ambitions had now come to fruition. In an article entitled “My Daly’s Dream” which was published in Music Masterpieces in 1936 he mentioned that, after seeing “The Country Girl”, his first experience of musical theatre, he one day wanted to write music for a Daly’s play. Here he was, at the age of 33 with his earliest dream realized.

“The Country Girl” had opened at Daly’s in 1902 and had run for 729 performances. The music was written by Lionel Monckton and was the first of his many hits. This suggests that a very precocious Marc had travelled to London and seen this show when he was barely a teenager. It is hardly surprising that his love of the musical theatre and London began at such an early stage and now, some twenty years later, his own music was being played at Daly’s.

“The Country Girl” had opened at Daly’s in 1902 and had run for 729 performances. The music was written by Lionel Monckton and was the first of his many hits. This suggests that a very precocious Marc had travelled to London and seen this show when he was barely a teenager. It is hardly surprising that his love of the musical theatre and London began at such an early stage and now, some twenty years later, his own music was being played at Daly’s.

On Boxing Day in 1925, it was announced that the New York producer, Arch Selwyn, was to sail for London to discuss with Cochran the transfer of On with the Dance to the States for an autumn 1926 production.44 This was clearly good news for Marc, whose music was now getting greater recognition on both sides of the Atlantic.

Marc was not only receiving newspaper coverage in England and in Scotland, where the press occasionally caught up with his progress, lauding his success as a former student of the Dollar Academy but, from time to time, papers in the Far East would comment on his musical achievements. The Shanghai Mercury even picked up a story from London’s Evening News about the Penang-born musician and his early struggles.45

In the early 1920s, as a relief from his hectic work schedule, Marc decided that he would open his charming Glebe Place flat, which could accurately be described as cozy, since it was certainly limited in space, to give a small children’s tea party each year. Marc, despite being a confirmed bachelor was, in fact, very fond of children and no doubt they enjoyed being fussed over by this young composer whose reputation was growing exponentially. His party in this year was held on January 4, 1926.46 He claimed that he did it because he was so fond of children but his cynical friends retorted47 that

He does it once a year so that he may gloat over his freedom during the remaining 364 days!

The institution of his Sunday tea parties had also been introduced in the same period and was to continue until just before his death. In fact, so well known had his soirées become that The Daily Sketch argued48 that

probably the most Bohemian parties in London are those given by Marc Anthony in his Chelsea studio. They are always held on Sunday afternoons.

A new and far more elaborate style of cabaret was to appear in 1926, in the form of a production at the New Princes Frivolities, under the direction of Percy Athos, who had also been responsible for presenting the reviews at the Rector’s Club. This was the spectacular production that went by the name of In Old Hankow. As London’s Evening News reported:49

there was a truly Drury Lane pantomime magnificence about the costumes and the show marked a further advance in the increasing elaboration of this kind of entertainment.

Many of the numbers for the show were composed by Marc and his widely popular highlight was “Silvery Dreams”, performed by the dancer and mimic Jean Rai.

So successful was In Old Hankow that, after its run at the New Princes, it transferred in September to the Finsbury Park Empire, where it continued to play to full houses. Marc’s music won plaudits in the press reviews and not just locally. The Scottish papers also recognized his talent, reporting, for example, that his “music has a swing and rhythm that make for instant success.”50

1926 continued to be a busy year for Marc. In September, de Courville asked if he could write an additional number for the show The Merry World, which was then playing in New York and was due to arrive in London. Marc had the tune in his head but had to phone the lyricist, Donovan Parsons, and play it over and over to him until the writer had the melody clearly set in his mind.51

In the following month some music he had previously submitted was included in Billy Merson’s musical comedy My Son John, which arrived in the West End after a preliminary tour outside London. The renowned Vivian Ellis wrote another piece in the show. Vivian Ellis was already a popular composer and was to go on to write “Spread a Little Happiness” and “This is My Lovely Day”.

In early November, yet another club opened its doors for night revelers in London. This was the new Lido Club and it was adventurously decorated in Italian fashion, with the orchestra seated in a gondola and a large canvas stretching behind the cabaret stage. Specifically for the Club, Marc composed some waltzes, which were used on opening and subsequent nights. According to the Manchester Sunday Chronicle, Marc “the brilliant composer, actually went to the Lido to get the right atmosphere in which to compose the Lido waltzes”.52

The opening night did not go without a hitch, however, as an injunction against the management regarding two of the numbers was threatened. So, after the public had left, Marc, the artists and the producer worked on replacing some of the music with substitute scores, which Marc wrote.53

Back at the Bullfrog Club, where Marc continued as ever to provide his music in his own characteristic manner, another move was on the cards. When he began at the Club it was at a premises on Sherwood Street, very close to Piccadilly Circus. In 1926, it moved to New Burlington Place. An autocratic but magnetic fixture of the Bullfrog was the owner, Emile, who was famous for having a rather droll sense of humour and for complaining that her clients were overstaying their welcome. Nevertheless, her attitude seemed not to discourage the customers and may well have been one of the reasons why they kept coming back. When the Club re-opened in New Burlington Place, Emile changed the name to the “Lamp Post Club”.

In 1927, Marc was to come into contact with the pinnacle of London’s theatrical royalty when he was asked to write special music for a Percy Athos presentation at the New Prince’s Frivolities of S. N. Behrman’s The Second Man. Produced by Basil Dean, who was to go on to become one of Britain’s great film producers, this comedy featured Noel Coward, Zena Dare, Raymond Massey and Ursula Jeans.54 The double bill, which was hugely successful, opened at the Playhouse Theatre on London’s Embankment and then, subsequently, transferred to The Hippodrome. As a result of their collaboration on this production, Marc and Noel Coward became firm friends and remained so until Marc’s death just two years before Coward passed away. Coward was often to be seen at Marc’s Sunday afternoon tea parties relaxing unceremoniously (and somewhat uncharacteristically) on cushions on the floor.

Towards the end of 1927, the score of a new musical comedy, The Cinderella Fellah, had emerged from Marc’s imagination and now only needed a production to see it flourish. The book was intended to be developed by Peter Jackson but was eventually written by Edward Dignon and Geoffrey Swaffer, who happened to be the brother of the art critic, Hannen Swaffer.55 It was at this time that Marc collaborated with Bruce Sievier, the racing correspondent of the Sunday Independent, to write some songs, one of which was called “I Thank the Moon” (see Appendix for sheet music) and which was to be included in the show and later published by Keith Prowse. Marc and Bruce were to go on to collaborate on many future numbers.

By the end of 1927, Marc had been living in London for seven years and had enjoyed a good deal of musical success with dozens of songs enjoying growing popularity. Of necessity he was augmenting his income by playing most nights in the cabaret clubs of central London. There was little doubt that his reputation was thriving and that he had cemented a position for himself in the musical dynamic of the city. His electric and charismatic personality endeared him both to the Bohemian as well as the more conservative layers of society.

It’s perhaps worth quoting from an article that was drafted by a London journalist (R. B-A.) in early 1928, in which he stated the following:

Mr R. Marc Anthony, a portrait of whom we publish here, is the only composer of truly melodious light music that the English stage has produced in the last decade. Each night Mr Marc Anthony is to be found delighting the only group of real Bohemians in London at the Bullfrog Club — where, as pianist and cabaret entertainer, he has earned a reputation that is absolutely unique in its popularity and this amongst those who are truly able to judge merit at its face value. Some of his ballads and dance music have already brought him considerable success and, indeed, he has been described by possibly our greatest librettist as the Jerome Kern of this country.

Carl Hentschel, the famed photomechanical technician, had started the Playgoers Club in 1893, as he was an avid theatregoer and professed to have attended every opening night in London.56 However, at some point, on a matter of policy, he and others split from the club and set up an alternative, known as the Original Playgoers (O.P.) Club and, as such, continued to hold annual dinners, attendance at which was very much in demand.

An annual dinner of the O.P. Club was held on February 1, 1928 at which the Prince of Wales was the guest of honour. Also there were Sir Charles and Lady Higham, Sir Frank Benson, Sir Edward Elgar, C. B. Cochran and numerous other major figures. Included in the list of attendees were Lilian Davies, the musical comedy star, and Marc Anthony of the Lamp Post Club.57

The Lamp Post Club continued to make its presence felt as one of the most popular dance venues and, according to the Melody Maker in its May 1928 issue, was a place where “you can get heaps of fun, good food and a drink to wash it down, all for a most reasonable sum”. Marc was appearing nightly with Lang Silvestre, the accordionist, and the caricature artist, Sava Botzaritch (Anastas Botzaritch Sava), drew a portrait of Marc at the time. It was Sava who had also drawn a caricature of Marc when he was at the Ham Bone Club. At the Lamp Post, Marc largely played waltzes but, when he “blossoms out into fox-trots, Lang plays drums”.58

In 1928 Marc also completed another musical comedy and he was looking for a name and a story when Adrienne Brune, the musical comedy actress, in her flat late one evening, sang two of the numbers. She was then appearing at the Pavilion Theatre but a year or so later was to appear in The Three Musketeers at the Drury Lane Theatre. Two of the numbers she sang that evening were “I Will Follow” and “Balalaika Music”.59 It must have been very satisfying for Marc to read a small article that appeared in The Penang Gazette60 saying that, “Mr Anthony, who left Penang some years ago to study music at Home, has justified his choice of a profession.”

The drama and music critic, Hannen Swaffer, referred to earlier, in one of his columns in September 1928, decries the fact that managers fail to look to Marc Anthony’s new work.61

I am assured that “Balalaika Music” will be a sensation … all it wants is a manager to take Marc Anthony’s music and Bruce Sievier’s lyrics and build up the rest.

Strange coincidences can be valuable or disastrous and Marc was faced with the latter when serious moves were made in 1928 to produce his music for The Cinderella Fellah. It turned out that, simultaneously, Owen Nares, Bobbie Howes and Binnie Hale were working on a production of Mr Cinders, which was based on the same concept of having a male Cinderella, although their interpretation was a straight play as opposed to Marc’s musical comedy version.

The Gallery First Nighters Club had become well established and was made up of highly respectable people consisting of62

young ladies whose soft accents are an echo of Mayfair and of young gentlemen of the literary student type, who discourse learnedly on Shavism and censorship.

On November 18, 1928, The Club held a special dinner honouring the actor Jack Buchanan at Frascati’s Restaurant in Oxford Street. There were speeches, and, of course, a who’s who of performers to provide the entertainment. Marie Dainton brilliantly mimicked Phyllis Dare, Evelyn Laye, Gracie Fields and others. Stanley Holloway sang two numbers and Adrienne Brune sang “I Will Follow”, accompanied at the piano by Marc.63

It was during this year that Marc became one of the first “stars” taken on by Marjorie Pratt, Countess of Brecknock, who had decided to go into music publishing and had taken a shine to Marc and felt that his music was exactly the sort of light stuff she was looking for.

Despite Marc’s continuing success in writing what many thought were great numbers, he simply wasn’t getting the traction he deserved and the blame for this was frequently put at the feet of managers who preferred to import American music, which they saw as safe and with greater profit potential. There was also the tendency for the BBC, which was broadcasting music for many hours a day by this time, to feature American rather than locally grown talent. Even the Brecknock’s Music Publishing Company had to take time on Paris Radio to get their English music played.

Perhaps Hannen Swaffer in Theatre World summed up the reality of what British artists were faced with in a brilliant opinion piece in mid 1930.64 Amongst other things he mentioned that

an American composer comes to London and stays at the Carlton Hotel, drives about in a Rolls Royce … peers and minor royalties entertain him and ask him to play after dinner … he earns £20,000 − £40,000 per year … why, Jerome Kern is so rich that even his collection of books fetched £360,000. … Irving Berlin is so wealthy … George Gershwin is a social lion … meanwhile the English composer is unrecognised. How can an English composer get work in England when the theatre is becoming more and more a branch of the American musical comedy trust? … Marc Anthony, one of the most brilliant young composers, is now playing the piano at Soso’s restaurant although his beautiful music has not been given a chance.

Swaffer goes on to say that

musical comedy today is not a theatrical show but a mere branch of the music publishing business and … ruined by song-plugging.

Hannen Swaffer was not the only voice crying out for a change but it seemed that it was all falling on deaf ears as the broadcasting industry was increasingly wanting to focus on one hit tune per show and then use the airwaves to plug it ad nauseam. Much the same call for light to be shone on British composers was raised in an article in The Encore in May,65 in which Bruce Sievier bemoaned the fact that “the theatre is dying!”. He went on to state

nothing is harming this country so much as the Americanisation of our youth, through the medium of the theatre and the picture-house.

As if to endorse these comments, the Winning Post the following year posited that

there are numerous composers in this country … amongst them Marc Anthony, who has a gift of melody better than that of Vivian Ellis and can produce more worldliness in his music.66,67

In the same vein, a Sunday Express columnist wrote that he had been asked to go to the Putney Hippodrome to hear a new British song by a young British composer by the name of Marc Anthony. He had, in fact written two numbers: “Shadows Around Me Blues” and “Step Out” which, according to the journalist “would have been the rage if they were composed by an American”.68

In February 1929, yet another new night club set up at No. 14, Ham Yard, Soho, called the “Blue Lantern” and was officially opened by Marc’s friend and actress Adrienne Brune. For a while, he took over the role of pianist at this club. In the writer Anthony Powell’s autobiography, Messengers of Day, he describes the place as fairly seedy; below the Gargoyle in status but, nonetheless, bearing a faintly intellectual tinge. Powell then goes on to celebrate the night at the club when the American actress Tallulah Bankhead asked him to dance with her.

Marc was continuing to write music and, by early 1930, was also playing at Soso’s Restaurant where Josephine Earle, with whom he had worked previously, was appearing. He had written several other pieces including “Lady of My Dreams”, which was to enjoy great popularity. Subsequently, Marc moved to the Bat Club in Albemarle Street.

During 1930, Marc’s connection with his alma mater, the Dollar Academy, was reignited when he was asked to compose the music for their school song (see Appendix for sheet music). The Scottish writer, poet and dedicated Highland hill walker, W. Kersley Holmes, who was also a former pupil at Dollar, wrote the lyrics.69 A “78” record was produced, which included, on the reverse side, a song called “Memories”, which had also been written by former pupils of the Academy. The noted baritone, Roy Henderson, sang both pieces.70

In June 1930, the dancer, Anton Dolin, returned to London from America to begin a season at The Coliseum with his company of 30 singers and dancers. Dolin and Marc had become close professional and personal friends over the years and this gave them both an opportunity to work together again. Several new musical numbers were specially written for the show, which was to be called Away From the Blues. Dolin and his corps de ballet were also to give an impression of bathing, tennis and golfing in the Deauville Beach scene from the Diaghilev ballet Le Train Bleu. Also on the bill was the comedian Jimmy Godden, who had been on tour in Australia and New Zealand. The review of the show in The Stage was encouraging and described it71 as

an entertainment that is notable for good work in every department and special effective staging and dressing.

One of the most celebrated restaurants in Paris that attracted and welcomed through its doors the Bohemian artists and writers living in or visiting the city was La Petite Chaise at 36 Rue de Grenelle. At the end of 1930, Marc took up winter residency for a while at this venue and presided at the piano from dinner into the early mornings.

Throughout 1931, Marc worked on the music for a new musical comedy picture to be called The New Hotel, with his friend Bruce Sievier writing the lyrics. When he heard the music, Liew Weir, general manager of Peter Maurice, the music publishers, professed, “Marc Anthony’s musical comedy score is one of the best I have heard for years”.72

The New Hotel, which was a production of the Producers Distributing Company, was filmed at the Stoll Studios in Cricklewood and had a cast of 45 with 120 extras. It only achieved modest success and the reviews were luke warm, with the London Picturegoer describing it73 as having a

negligible story but that the turns, which include an excellent apache dance and some trick roller skating, are very good of their kind.

But in February 1932 Marc had another musical challenge, which was to provide the accompaniment to a rather extraordinary fashion show. Starting with a scantily clothed Eve, the collection by Val St Cyr of the House of Baroque, was creative, at times outrageous and certainly got the notice of the press and fashionistas from all over Europe. Marc’s musical score was to the words of “Meet My Mannequins”, which the designer himself presented. The Duchess of York and many other society and show business celebrities attended the event.74

A new and original review under the title of After Dinner saw its opening at the Gaiety Theatre in October 1932 after having pre-West End previews at the King’s Theatre, Southsea, in Leeds and Birmingham. It had a stellar cast and Marc wrote much of the music for the programme. Among the cast were Hermione Baddeley and Gwen Farrar, who also devised the show. Marc’s songs included “After You’ve Dined”, “Step Out”, “Shadows” and “There’ll Always Be a Sally”.75

1932 was a year of travel for Marc as at some point he travelled to the Far East and Australia, returning to London aboard the “RMS Corfu” from Brisbane on August 23 in that year, listing himself on the passenger manifest as “artist”.76

However, in the same year he also took himself off for a vacation in Tangiers, which had become a popular destination for the London set to go and let their hair down and enjoy an often self-indulgent escape, less worried by the more straight-laced mores of English holiday resorts.

He returned to the Bat Club in February, 1933, which held a special Marc Anthony Night celebration “to welcome his return to the fold after wandering in the wilderness”.77

Marc’s night club duties continued and even increased during the early 1930s and he was to be found not only at the Bat Club but also at the Cossack Restaurant in Jermyn Street, where he performed in the Cossack Bar during cocktails and then again in the restaurant at midnight. Marc’s musical attachment to the Cossack was to last several years.

He was also for a time the resident pianist at the Dorchester Club in Grafton Street and made special appearances at others, such as Ciro’s Club where, in November 1933, he accompanied Anton Dolin in his “Song of the Dance”.

In February 1934, Margaret Cochran sang some popular numbers accompanied by Marc in “Our Cabaret” at the London Pavilion and, in the same year, Marc was one of several artists to perform before the soon-to-be Queen Elizabeth at Dean’s Yard, Westminster, at a market held in support of the Westminster Hospital rebuilding scheme. On this occasion he played one of his own compositions for the future Queen and her retinue.

In October, Cecily Debenham, regarded as one of the great comediennes of her time and about whom P. G. Wodehouse had referred in his correspondence about Marc some fourteen years previously, was holding a party at her house in Connaught Square at which Marc had been invited to play. He performed music to a new show he had written with Bruce Sievier based on a book by Frederick Carlton. Once again, everyone agreed that they were listening to a very talented musician who should have been enjoying the financial fruits of his success and not augmenting his income by playing in night clubs and restaurants, no matter how much he enjoyed doing so.

At this time, during one of his sessions at the BBC, Marc was to befriend a young performing prodigy, who was later to become one of England’s most famous broadcasting stars. In 1935, the teenage Hughie Green was appearing in a BBC show and touring with his all-children cast concert party. On the reverse of his signed photograph, Hughie wrote:78

14 years — my first evening dress suit. This I had made when with the “Gang”, made my first stage appearance.

June 1936 was to see Marc at the Grosvenor House Hotel accompanying Anton Dolin once again in a selection of gracefully athletic dance routines. Jack Harris’s Grosvenor House Band was a regular at the Park Lane hotel and, after the more sophisticated music of the evening in the restaurant, the hotel opened its ballroom to the Midnight Vanities, which was normally a far more energetic show than Dolin’s and certainly displayed a greater amount of flesh!

Shortly after this show, in August, Marc played as guest pianist at a review in Copenhagen, Denmark, using some of his own music.

Television was beginning to appear in our homes but only just. At the beginning of 1937 there were only 400 receivers in the country but, by the end of that year, this had grown to around 2,000, many of which were bought by businesses, such as hotels and bars, as they saw the opportunity of providing an additional attraction for their customers. Marc had already appeared on the radio in a programme entitled “Songs You Might Never Have Heard”, in which one of the numbers he played was “Deep Dream River” (see Appendix for sheet music), which one reviewer regarded as “a pippin of a song”.79

The BBC only broadcast from 10:00 in the morning to closedown, which was at around midnight. The programme in the afternoon at 3:00 was usually a short feature on a range of subjects from fashion to health exercise or snooker. But occasionally they had a performer and, in April of that year, they had already broadcast short performances by Ingrid Lincke, soprano, and Fredrika, mezzo soprano. On Thursday April 29, in a programme entitled “The Composer at the Piano — Marc Anthony”, he played some of his melodies.80 The following month, of course, the BBC produced its first outside broadcast, which was the Coronation of King George VI.

Marc worked with his good friend and colleague, Anton Dolin, during 1936 and 1937 on a new show that the Markova-Dolin Ballet was producing as part of the Company’s Coronation Season, which saw it appearing both in the UK and overseas and which would include Markova and Dolin themselves and Dolin’s new pupil, Belita, dancing to Marc Anthony’s “Debut”.

The extravagantly named Maria Belita Gladys Olive Lyne Jepson-Turner was professionally known as Belita, and was a British Olympic figure skater, as well as being a dancer and actress. At the end of 1936, she represented the UK at the Winter Olympics in Bavaria in the Ladies’ singles competition, ending up in 16th place.81 The cast of this show contained the crème de la crème of the ballet world. Apart from Markova, Dolin and Belita, Serge Lifar, from the Paris Opera, performed an excerpt from “L’Apres Midi d’un Faune” and Lydia Sokolova danced Rossini’s “Tarantella.”

Prior to this season of shows, in which was included “A Poem”, specially written by Christopher Vassal and spoken by the actor, John Gielgud, Dolin and Marc travelled to Venice to stay at the Excelsior Hotel before heading off for a few days in the Austrian Tyrol.

At the end of 1936, Marc asked Eric Maschwitz, head of the Programme Division at the BBC, if he would like to hear his score of a musical play Maschwitz had written called Balalaika. However, on receiving it and reading the libretto, Maschwitz responded by saying that he did “not think it in the least suitable for broadcasting” and that it did “not contain any startling novelties nor is the dialogue particularly outstanding”.82 Despite the popularity of his music in the nightclubs and on stage, it did not seem to receive the same degree of enthusiasm from the broadcasting media.

There is a touch of irony in the fact that Marc was later to become a good friend of Hermione Gingold, who, at this time, was married to Eric Maschwitz, but from whom she divorced in 1945.

Despite the rejection of his music by the BBC, this did not prevent Marc from doing the occasional radio and television appearances but they were more often than not in the form of an interlude between programmes. An example of this was on September 30, 1937, when he appeared briefly for a 5-minute session, playing his own repertoire, between “Round the Film Studios” (a visit to Pinewood to watch the making of a picture) and “Clothes-Line 1” (discussing the importance of dress!).

In December 1936, The Blue Circle Players put on a production of The Late Christopher Bean by Emlyn Williams (from an adaptation from the René Fauchois comedy), at the Arts Theatre Club. The fact that Marc played at the piano during the intervals was of particular interest but of even greater significance was the fact that, many years prior to the legal prohibition of smoking in theatres in the UK, smoking was actually not permitted in the auditorium at these performances. This must have marked a first for the theatre industry.83

And so the war years came and, as for everyone else, Marc’s career took a significant hiatus. Many clubs were closed and those that stayed open were curfewed early. Some theatres went dark and those in the performing arts had to face even greater struggles than before.

Marc was always prepared to offer praise and good wishes to others in the music and theatre industries and he sent a letter to Ivor Novello on the opening night of his new show The Dancing Years in March 1939. The show was to go on to enormous success, even after having to close at the outbreak of war and not reopen until 1942. Novello graciously responded in a letter to Marc shortly after the opening.84

Marc was always prepared to offer praise and good wishes to others in the music and theatre industries and he sent a letter to Ivor Novello on the opening night of his new show The Dancing Years in March 1939. The show was to go on to enormous success, even after having to close at the outbreak of war and not reopen until 1942. Novello graciously responded in a letter to Marc shortly after the opening.84

This is not to say that, despite the outbreak of war, there were no opportunities and Marc was able to find venues in which he could work, notably “The Spotted Dog” in Bruton Mews, which catered particularly to members of the armed forces. It was in this club in October 1940 that he was one of the victims of a bombshell, which destroyed the club and sent him and many others to hospital. Two died, but he was fortunate to have survived. Ironically, he had just finished a set and left the piano to join some friends for a drink, when the bomb landed and the piano took a direct hit. It turned out that the man who rescued him was Peter Churchill, a member of the Special Operations Executive and a highly decorated officer.

The bombs may have been falling on London and evidence of the struggle against the enemy was everywhere, but that did not stop ordinary people from trying to live as normal a life as possible. In 1942, a friend of Marc’s drew a rather simple but touching picture of him in his small bedroom at Glebe Place. Marc, as with the rest of the stoic British, needed their relief from the ghastliness of war. During this time, dance halls, theatres, picture houses and other entertainments did continue to survive the onslaughts of the enemy.

The bombs may have been falling on London and evidence of the struggle against the enemy was everywhere, but that did not stop ordinary people from trying to live as normal a life as possible. In 1942, a friend of Marc’s drew a rather simple but touching picture of him in his small bedroom at Glebe Place. Marc, as with the rest of the stoic British, needed their relief from the ghastliness of war. During this time, dance halls, theatres, picture houses and other entertainments did continue to survive the onslaughts of the enemy.

In April 1942, the Vaudeville Theatre on The Strand featured Scoop, a production by Henry Kendall. The show was filled with contemporary stars, including Kendall himself, Charles Hawtrey, Nadine March and Joan Winstead. Though Arthur Young wrote most of the music, there was a wonderful section written by Marc called “Vienna Will Dance Again” with dialogue by Alan Melville.85 Ironically, in 1936 the BBC had offered Melville a job as scriptwriter in the variety department under Eric Maschwitz, the man who had previously turned down Marc’s Balalaika at around the same time. Melville was to go on to become one of the BBC’s most recognised broadcasters.

The following year, Prince Littler presented a show at The Coliseum called It’s Foolish but It’s Fun in which Jimmy Nervo and Teddy Knox starred. For the first time, Marc was billed together with such musical contemporaries as Vivian Ellis and Ralph Reader. This show was to find great success not only in England but also on a worldwide tour, which went as far as Australia.

Marc had remained friends with the actress Lily Elsie, whom he had come across first when he saw her on the stage in London in the first productions of The Merry Widow and for Christmas 1940, he sent her a box of chocolates, which she clearly enjoyed even though she was “steadily putting on weight”, according to her letter of thanks to him.86 In the letter she also refers to a “sweet letter” from Anton Dolin. She ended the letter by wishing him

every good thing possible for 1941 and may it be a crushing one to Hitler and Co that will lead to our victory and peace to the world.

One of the show business personalities with whom Marc had become close over the years was the comedian Leslie Henson. Henson was to organise, with the assistance of Basil Dean and Sir Seymour Hicks, the Entertainments National Service Association (ENSA) and one of their shows came to be called Gaieties. He took his show across the globe during the war and, at one of the performances in Scapa Flow, King George VI, together with other senior officers, was shown in a photograph being greatly amused by one of Henson’s jokes.87

Shortly after the war, Marc found himself in America, where he performed as a guest artist for several months in various night venues. He left Southampton on the United States Lines “MS John Ericsson” on May 20, 1946.88 He arrived in New York 10 days later. This was the final voyage of that ship in its guise as a troop carrier, as such making 27 journeys across the Atlantic in the latter stages of the war.89

While in New York, where he accompanied Dolin and Markova (as New Yorkers fell in love with their performances), he also found time to be the tourist, visiting the Statue of Liberty and watching a performance by Ethel Merman in Annie Get Your Gun. He was also to visit the Stork Club and see a revival of Oscar Wilde’s Lady Windermere’s Fan, in which the photographer and artist, Cecil Beaton, made an appearance in the part of Cecil Graham. Marc returned to London on the same ship “John Ericsson”, which, in the time that Marc had been in the United States, had become part of the Panama Pacific Line.90

On January 7, 1949, Anton Dolin and Alicia Markova and their corps de ballet appeared at Earls Court with the Philharmonia Orchestra under the direction of Muir Matheson. One of the very many signed pictures of Dolin in Marc’s collection is the one with him and Markova, inscribed simply, “For Marc. Blessings”.

On January 7, 1949, Anton Dolin and Alicia Markova and their corps de ballet appeared at Earls Court with the Philharmonia Orchestra under the direction of Muir Matheson. One of the very many signed pictures of Dolin in Marc’s collection is the one with him and Markova, inscribed simply, “For Marc. Blessings”.

As well as Anton Dolin and Alicia Markova, Nathalie Krassovska and John Gilpin were part of the first London season of the Festival Ballet. Marc attended several of the rehearsals and was invited as a guest for the opening night which was so successful that it became instantly clear that this new company was going to go from strength the strength, which indeed, it did.

Because music was his life and his inspiration, any opportunity that arose, Marc would stride to the piano and do what he did best — entertain. At a party in September, 1952, in Belsize Park, at the home of the opera, theatre and ballet designer, Tom Lingwood, he was playing throughout the night while Anton Dolin looked on and John Gilpin of the Festival Ballet sat on the hearth rug and Dame Laura Knight, the consummate artist, watched from the back of the room.91

In April 1953, Marc’s friend and fellow artist, Bruce Sievier, died. The man who had written the lyrics to “I Thank the Moon” and “Deep Dream River” and several other of Marc’s melodies, was found in a gas-filled room in Golders Green. It was well known, particularly amongst his drinking friends at The Tin Pan Alley Club in Denmark Street, that the “Gentleman of Tin Pan Alley” was short of money. But it is supposed that nobody had realised just how depressed he had become. Sadly and too late, only a few hours after his death there was news that he had been sent $500 from America for his “Valse Vanity” and also his agent received confirmation that his latest song “I Live Every Day With You” was to be published.92

The London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art held its annual Revue in July 1953. In a wonderful twist of fate, the man who had left Penang to “study music in London” but had not done so; had chosen to invent his own musical vocabulary; continued to play by ear and memorise tunes; become the “King of the Night Clubs” and make a name for himself as a writer of waltzes and fox-trots, was to be asked to accompany the actors and singers in their graduation performances at LAMDA. One has to believe that Marc smiled ruefully to himself as he carried out his duties on this important occasion at the Academy’s Logan Place theatre.

From 1956 Marc was appearing nightly at the Braganza Restaurant in Soho but his health was not as good as in previous years and the late nights were taking their toll. However, he remained the artist in residence there for the next four years.

Marc’s love of the musical theatre and the fact that, from his schooldays, he had attended performances wherever and whenever he could, was to be epitomised in his life long love affair with Franz Lehár’s The Merry Widow. Back in 1905, Lehár was to bring the true Vienna back to life with his new operetta and Marc was drawn to it from the very beginning. In fact, he was to attend every first night of every London production of The Merry Widow throughout his life. The Music and Musicians magazine interviewed Marc for its April 1958 edition, in which he reminisced about the first London version with Lily Elsie, with whom Marc was to work and with whom he was subsequently to become a very close friend for many years.93

Marc also knew Lehár himself and, in fact, the composer sent Marc a postcard on April 26, 1925, on which he had written the opening bars of the Serenade from his operetta called Frasquita, which had its London premiere that year and in which Richard Tauber appeared.94

Marc also knew Lehár himself and, in fact, the composer sent Marc a postcard on April 26, 1925, on which he had written the opening bars of the Serenade from his operetta called Frasquita, which had its London premiere that year and in which Richard Tauber appeared.94

In 1960, Marc began work on the score of a new musical play, which he called Chance Meeting. The book and lyrics were by Philip Carr. While he was working on this, he was performing at a new venture in Jermyn Street called the 55 Club, which was run by David and Virginia Hamilton and it was at that time the nearest thing to a Continental style bar restaurant to be found in London. Now Marc was no longer playing in the post midnight sessions but appearing at cocktail time and, according to Douglas Sutherland of The Tatler & Bystander, his music was well appreciated by those coming to the club after work or prior to dinner.94

Within a few months, it was clear that Marc required something even gentler to see him into his twilight years. After all, he was now approaching 70 years of age and he had been performing for his different publics for nearly fifty years. The Rockingham Club in Archer Street catered to those of alternative life styles and was certainly an attractive and popular venue. Pots of flowers and striped wallpaper greeted one on entry and there were numerous sporting prints and one large picture of the St Leger winner, Rockingham, after which the club was named. It was elegant and not inexpensive and attracted a good cross section of “high society”.

The Rockingham, which achieved its own celebrity status and was a well-known destination for an extensive and high-powered membership, was to be Marc Anthony’s final working venue and he played there until only a few months before his death in 1970.

Looking back on a life dedicated to music and the thrills and disappointments of composition, it is perhaps ironic that one of the most memorable aspects of Marc Anthony’s life lay not only in his melodies, nor the clubs and restaurants in which

he thrilled his clienteles, nor even in the all-too-brief fame that he achieved with his wonderful songs, but in the social milieu of Chelsea and its environs and in his extensive coterie of entertainment industry friends.

As we have discovered, Marc moved into Glebe Place in 1920 and lived there for 50 years until his death. He witnessed the enormous changes in London through the Depression, the two Great Wars and their repercussions and the changing scenes of the King’s Road throughout those times, including the Hippie movement of the 1950s and the punk culture of the 1960s.

Marc’s charismatic and endearing personality has been referred to but the result of this was the way in which he was able to draw people from all walks of life towards him as if in a universal orbit to his nucleus of calm.

As mentioned above, one of his greatest personal and professional friends was the great dancer, Anton Dolin, with whom he worked periodically over the years. Pat, which was his middle name and by which he was more intimately known, was a staunch admirer of Marc and encouraged him when he was failing to get his music performed or even accepted by publishers.

Both followed each other’s careers with the greatest of pride in their respective areas and Pat was an ubiquitous supporter of Marc and his talent. Although Dolin’s career took him around the world and he spent much time across the Atlantic, particularly during the time that he and Alicia Markova joined forces with their own touring company, whenever he was in London, he would meet up with Marc. Even on the occasions that he was overseas, he would keep in touch.

On one occasion, in 1951, when he was dining at the Grand Hotel in Venice with the multi-talented American actor, Gene Raymond and the actress, Jeanette MacDonald, he sent Marc a postcard signed by them both and adding:

On one occasion, in 1951, when he was dining at the Grand Hotel in Venice with the multi-talented American actor, Gene Raymond and the actress, Jeanette MacDonald, he sent Marc a postcard signed by them both and adding:

I knew you would like this. They lunched with me today. See you soon. Love, Pat.

Doubtless, Dolin knew that the connection with The Merry Widow, the 1934 film of which Jeannette MacDonald had appeared in with Maurice Chevalier, would have appealed to him.96

Again, in 1955 — the same year he was a guest on Roy Plomley’s “Desert Island Discs” on the BBC — from Paris, Dolin sent Marc a copy of the mouth-watering menu from Le Cabaret on the Champs Elysees. Apart from being an extraordinarily hedonistic display of the best of French cuisine, the menu was signed not only by himself but also by John Gilpin, the premier dancer of The Festival Ballet and also a life long friend of both Marc and Dolin, and Muriel Bentley, the Jerome Robbins dancer.97